Kidney Disease in Dogs

Article

As dogs age, they are at more risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) – a persistent deterioration in kidney function that is thought to affect one in ten dogs over the age of fifteen1.

Although CKD is incurable, early intervention can help to slow the rate of kidney damage.

In this article, we look at the causes and signs of kidney disease in dogs, the methods of diagnosis, and review some of the available options for management of the disease. But first, let’s talk about why the kidneys are essential.

Kidneys: The Body’s Filtration Factories

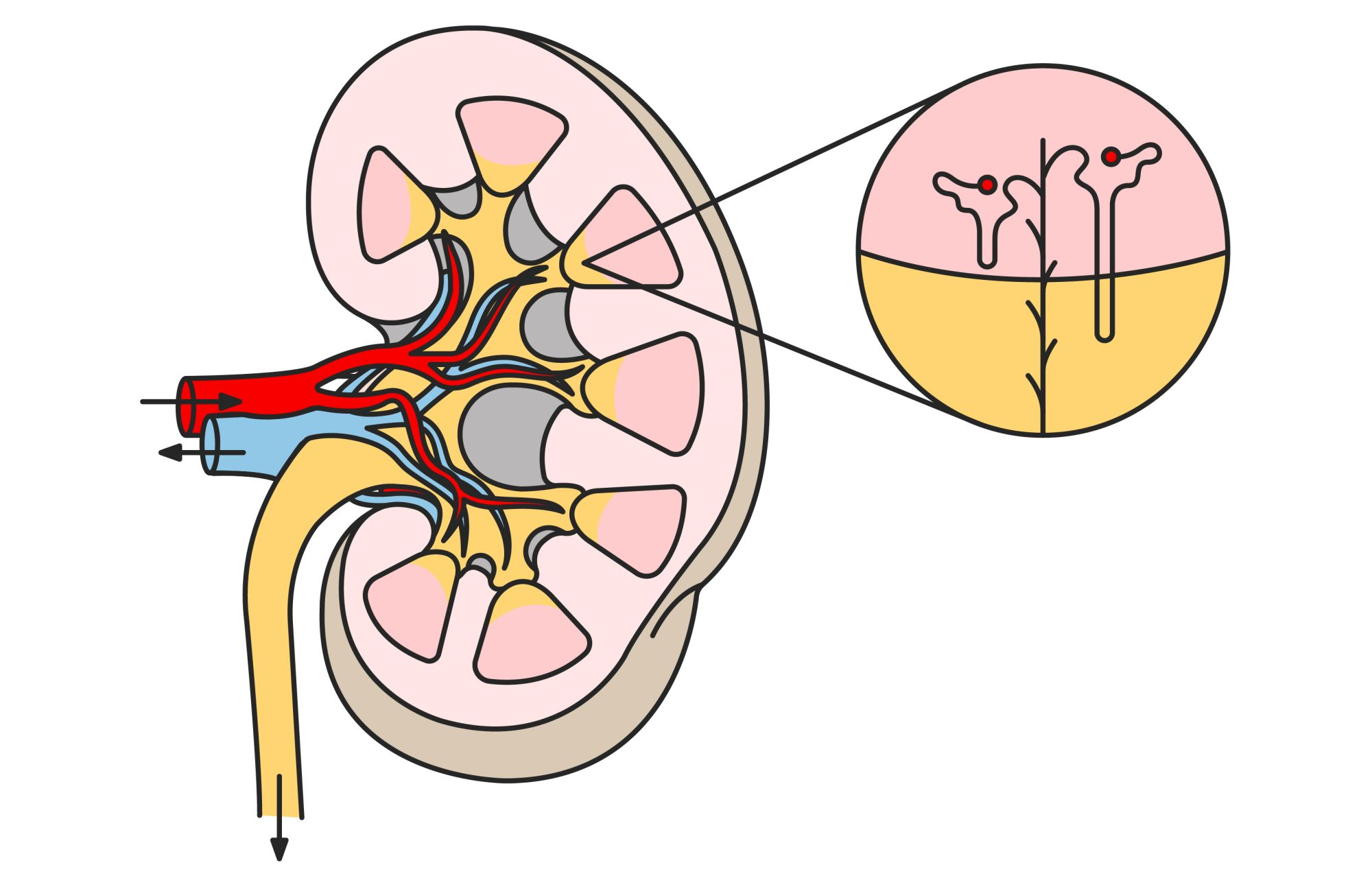

Dogs have two kidneys, just like we do.The kidneys’ job is to create hormones, balance fluids and manage blood pressure in the body. They also filter the blood to remove toxic waste products and recycle beneficial substances like amino acids and minerals.

When the kidneys stop working as efficiently as they should normally, the resulting condition can be either acute or chronic.

Acute Kidney Injury (AKI)

Also known as acute kidney failure, an AKI is a sudden loss of kidney function that causes waste products to rapidly accumulate within the body. It’s usually caused by trauma, infection, sepsis, loss of blood supply or the ingestion of toxic substances.The severity of AKI ranges from minor loss of kidney function to complete renal failure, but the condition always requires immediate medical attention. Although dogs can recover from an AKI, it puts them at a higher risk of developing CKD in the future, especially if they experience multiple AKIs.

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

In this article, we’re focusing on CKD, which is a gradual loss of kidney function that takes place over many months or even several years.It’s caused by a loss of nephron function, the microscopic filtration units inside a dog’s kidneys. Without enough filters, the toxins and wastes that are normally removed from the bloodstream accumulate.

Unfortunately, kidney tissue is irreplaceable and so a loss of nephron function can lead to CKD, a self-perpetuating condition that unfortunately has no cure.

What are the Causes of Dog Kidney Disease?

If your dog does develop the condition, it may be because of:

An acquired disease

Aging

About Chronic Kidney Disease

A disease is chronic when it develops over a long time and in the case of CKD, the dog’s signs and the management they need will all vary depending upon the level of kidney damage that has occurred.To help you and your veterinarian track the progress of the condition, CKD is separated into 4 stages known as IRIS (International Renal Interest Society) stages2, from 1 at the onset to 4 at its most severe.

The speed at which a dog progresses through the four stages varies depending upon how early the condition is diagnosed, the management they receive and their individual physiology.

What are the Signs of Chronic Kidney Disease in Dogs?

Once kidney tissue has been destroyed, it cannot be replaced or regenerated.

The kidneys account for this by having a large amount of spare capacity, consequently, the visible signs of CKD don’t present themselves until at least 75% of kidney function has been lost.

A dog may live with CKD for many months before the signs begin to appear, but some of the common signs you may notice include:

- Urinating excessively

- Drinking a lot of water

- A loss of appetite

- Weight loss

- Lethargy

- Vomiting

- Weakness

- Diarrhea

If you’d like to learn more, see our article The Signs of Chronic Kidney Disease in Dogs.

How is Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosed in Dogs?

Traditionally, veterinarians diagnose CKD by looking at the concentration of creatinine in a dog’s blood and checking for protein in the urine. They’ll also analyze their Urine Specific Gravity, as dogs with CKD have trouble concentrating urine.

However, just like with the visible signs, many of these tests only detect evidence of CKD when a considerable amount of kidney function has been lost – usually around 75%.

In the last few years, a new blood test has been developed to identify elevations in SDMA (Symmetric Dimethyl Arginine). When used in combination with serum creatinine tests and urinalysis, SDMA testing may help identify CKD when only 25% of kidney function has been lost3, which may allow management of the disease to begin significantly earlier than previously would have been possible.

Veterinary check-ups are an essential part of achieving an early diagnosis and so it’s important to take your dog to the veterinarian regularly, whether you suspect CKD or not.

How is Chronic Kidney Disease Treated?

The first goal is to treat the underlying cause of CKD, but in most instances, it will never be identified. Consequently, the main aims of CKD management are to preserve the dog’s quality of life, slow the progression of kidney damage, and manage the clinical signs as they appear.

Management for CKD varies depending upon the stage of the disease, but you can support your pet at every stage by:

- Making sure they always have plenty of fresh water

- Maintaining their oral health

- Taking them to the veterinarian for regular monitoring

- Being alert for new signs that may show the disease has progressed

Your veterinarian may recommend a low-protein diet with a high-energy density that is specially balanced for dogs with CKD who also have a loss of appetite. To encourage eating, these diets also offer a range of wet and dry options, with different aromas, kibble shapes, flavors, and textures.

You can discover more about the role of nutrition in the management of CKD in our article Your Guide to Renal Diets for Dogs with Kidney Disease.

As mentioned previously, IRIS has established internationally recognized guidelines on the diagnosis and management of CKD disease. Your veterinarian will assess which IRIS stage your dog is currently in as this will help them recommend appropriate management.

IRIS Stage 1

Typically, a veterinarian will recommend a special renal diet for dogs with CKD to control the amount of phosphorus they consume.IRIS Stage 2

One of the hallmarks of CKD is the build-up of toxic material in the bloodstream as a result of protein breakdown. To help limit the accumulation, an additional change of diet is needed at stage 2 to restrict the dog’s protein intake in addition to phosphorus restriction.IRIS Stage 3

The clinical signs of CKD become more apparent at IRIS Stage 3 so a veterinarian will take active measures to manage these signs, such as recommending medications to lower blood pressure or making additional dietary changes to optimize potassium levels.IRIS Stage 4

At the final stage, the signs of CKD become more evident and further management will be needed to correct the associated health issues. Management may include intravenous fluids, feeding tubes, and medications.While there’s no cure for CKD, and the early signs are challenging to spot, a dog can live with the condition for many months or even several years if they receive an early diagnosis and the appropriate treatment. That’s why regular veterinary appointments are so essential. If you have questions or concerns about CKD, speak to your veterinarian.

References:

1 Polzin DJ. Chronic kidney disease. In Bartges J, Polzin DJ, editors. Nephrology and urology of small animals. Ames (IA): Wiley Blackwell, 2011: 433-4712 "IRIS Staging of CKD." Iris Kidney, http://www.iris-kidney.com/guidelines/staging.html

3 Hall JA, Yerramilli M, Obare E, Yerramilli M, Melendez LD, Jewell DE. Relationship between lean body mass and serum renal biomarkers in healthy dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29(3):808–814.

Related Articles

Like & share this page